Lions & Tigers & Mics

Oh my!

Why do microphones in opera scare people?

I think it's because too many of us believe the myth that opera is an acoustic art form. Perhaps it was once upon a time, but if you've gotten out and about in the last thirty years, you may have noticed operas are being mic'd.

Or maybe you haven't and this blog will be a bit of a (R)evelation...

Sanford Sylvan, one of America's great baritones, told me about the world premiere production of "Nixon in China" at the Houston Grand Opera late one night at our dining room table in Montreal. He explained how the orchestration at the sitzprobe had overwhelmed all the singers and it became clear that they were not going to be heard. At all. And so Adams asked that the singers be amplified. So they did, without any fanfare.

Which was the opposite of what Paul Kellogg did when he was the general director of the New York City Opera earlier this century. Announcing to the press that since the State Theatre had been designed for ballet with acoustics to keep sound on the stage to a minimum (to muffle the feet of the dancers), the theatre was simply not suitable for opera. So they were going to amplify the voices. I heard a lot of shows in that theatre during those years, and the mic'ing was helpful to be sure. But the sound designers often didn't understand how much was too much, or sometimes even how to get the voices to not sound like they were coming from house left while their bodies were way over on the opposite side of the stage.

Many other companies started amplifying voices, usually without wanting anyone to know. Lots of rumors about mic'ing at the Met for some singers (mic'ing Anna Netrebka in "War and Peace" is now an urban legend), and I've personally witnessed sound boards in operation at the back of the houses in Houston, Minneapolis, Montreal, and Chicago.

When the NY Phil decided to produce Camelot and other musicals in semi-staged concert format, it surprised no one that they were mic'ing and amplifying their singers. Why amplify Nathan Gunn as Lancelot? Well, because others were and if you mic one, you kinda have to mic them all. Plus, once you mic the singers, you need to mic the orchestra. And then you need a competent sound designer to make it all sound natural.

So why are people surprised that Bryn Terfel was mic'd when he sang Sweeney Todd in "Sweeney Todd" at the Lyric Opera of Chicago? He has a big voice, he sings Wagner dontcha know! Well, it's because Sweeney has dialogue over music that easily overwhelms any performer. To be heard they'd have to shout their lines, which isn't what anyone wants. Aaron Tveit, who just closed as Sweeney on Broadway, actually has quite a full, acoustic tenor voice. I've heard him sing Rodolfo (yeah, Puccini's) and he could easily have had an operatic career. Same for Zach James, who is currently Hades in "Hadestown" in London, before he got on to the Broadway stage, he had a viable career in opera, still does in fact, singing operas all over the world. There are many others - Audra McDonald and Kristen Chenoweth spring to mind. Mic'ing is often a stylistic choice, and certainly when you've got a rock show or big heavy brass or synthesized sounds in the orchestra, mic'ing makes sense. It's not about the size of the voice...

Mic'ing, when done well, allows a sound designer to pick up the natural, acoustic sound of the voice and amplify it into a theatre space, mixing it with the other singers and the orchestra.

It doesn't change the voice all that much except to make it louder, unlike when a sound recording engineer is manipulating a singer recording a new classical album. Read that sentence again.

I find it ironic that the same classical purists scream "heresy" about employing mic's in a theatre, but go mute (and ignorant, to be frank) about the mic'ing and mixing that happens when they themselves, or other classical singers, record an album of Poulenc or Schubert songs. Those voices get altered on a massive scale, the balances between piano and singer are false, and the acoustic of the space it was recorded in can be varied electronically to make the studio sound like Notre Dame or an Esterhazy salon in rural Austria.

When singers sing outdoors, mics are used almost 100% of the time. That's okay with everyone it seems. Indoor or outdoor Arena productions also require mic'ing. Again, totally okay. So why, I must ask, is there this allergic reaction to mic'ing in a theatre where opera is concerned?

In a theatre, the mic'ing augments what the singer is putting out into space, capturing it and re-routing it into the amplifiers, along with the orchestral sound and any one else onstage. I find this kind of amplification to actually be quite honest, from the standpoint that you can really hear what the singer is doing. It exposes the sounds being produced, much like what we experienced teaching on zoom during the pandemic. The microphone gets up close and personal.

So advice to those clutching their pearls: Chill. Relax. No one is going to alter their technique and lose the ability to sing a legato phrase or a Mozart aria. In fact, when done right - with correct training - a singer can take some of the pressure off of themselves to create the decibels needed to sing through heavy orchestration. Often, there's a sense of "taking it easy" and singing at 75% instead of pushing into 125% with their voice. Diction, or the lack thereof, gets revealed.

Singing with mics can be quite helpful when viewed in a certain light. True, the battery packs can be annoying, as can the tape on the face, or the wires running up and around or through your hair/wig. (I really don't like seeing mics taped to faces, but that's me.) But many singers are already experiencing these mics when their show gets a webcast. Lavs (body mics) are very helpful for webcasting to pick up individual voices if you're mixing the webcast (something we do at McGill in order for the sound recording students' education.)

What isn't helpful is for the old guard who sang opera "the right way - without mics!" to make their students afraid or upset that mic'ing might be employed. It sets up a lie for young singers to fall prey to: opera is always acoustic. If you're doing so, please stop. You're not helping, you're just looking old and out-of-date.

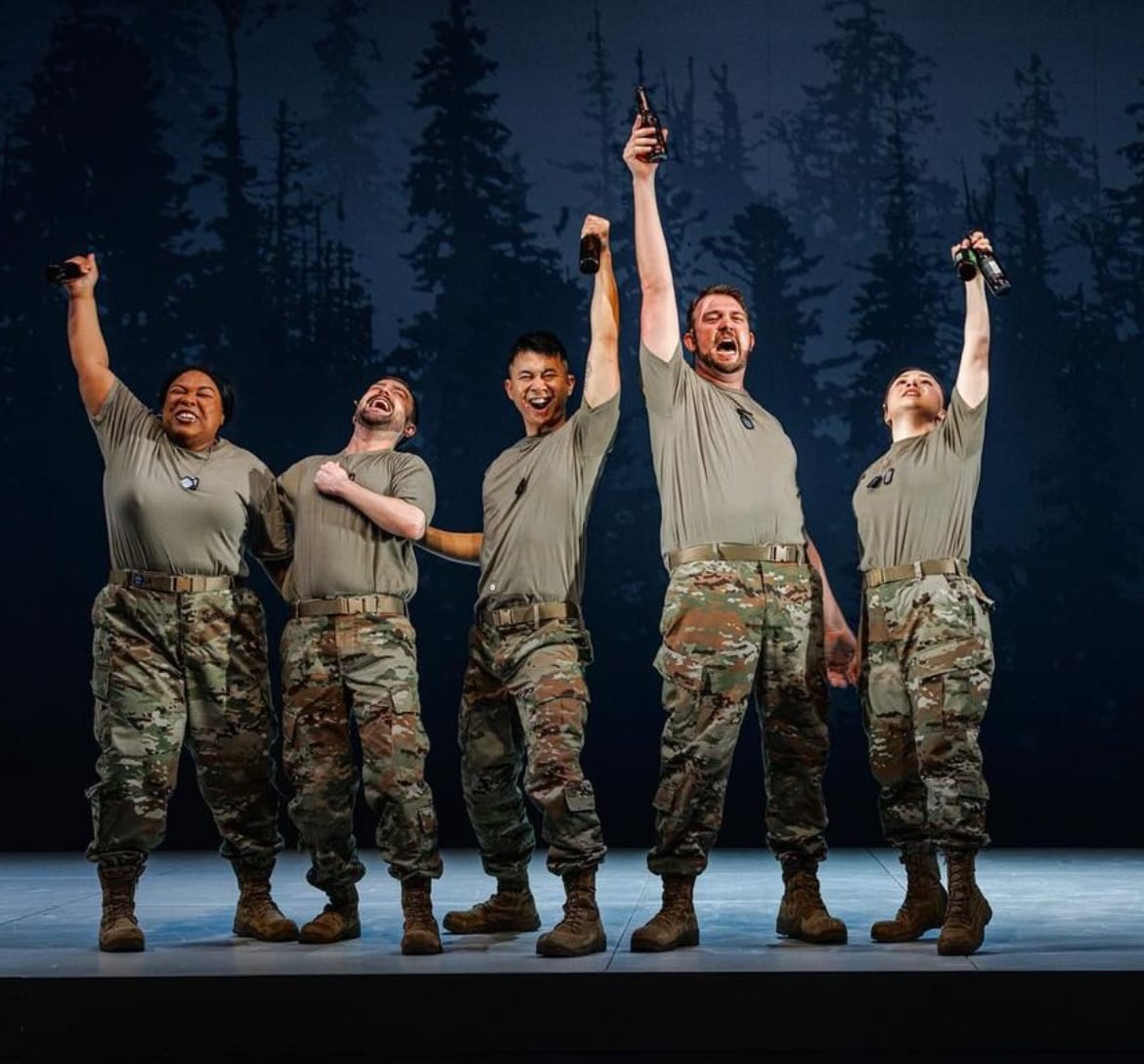

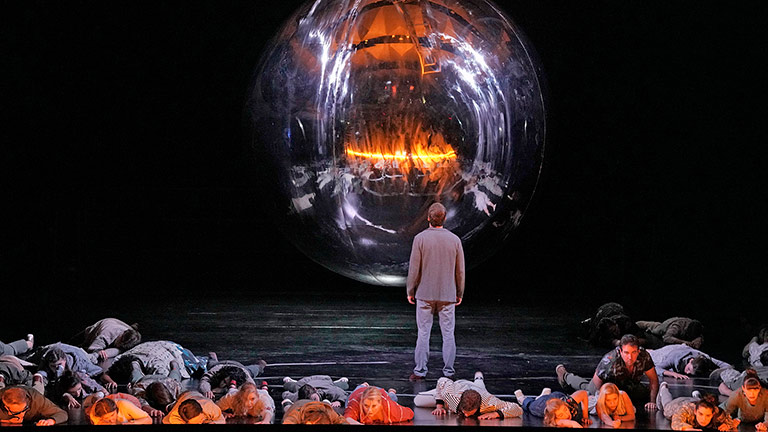

Maybe the following is news to you, but more and more contemporary operas are requiring mics; they are being written with mic'ing as part of the aesthetic from the get go. As well, more and more opera companies - from LA Opera to the Lyric Opera of Chicago - are producing musicals cast with opera singers (Renee Fleming in "The Light in the Piazza" is just one example). So mics are here to stay. Here's a bit of recent proof showing clear usage of mics - Broadway style (in plain view of the audience) from the world's operatic stages:

And here's a great tech article about what they did for Santa Fe Opera's production of John Adam's "Doctor Atomic":

And here's a pre-Pandemic blog from Seattle Opera explaining why amplification was used for their production of "The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs":

So, my friends. Amplification is here to stay. It will evolve as the technology evolves. I'm sure that decades from now, almost all opera will be amplified because our audiences will expect to hear "live" music differently.

Do I have any advice for a singer who's never been mic'd?

Yes – Sing just as if you weren't mic'd. Don't alter anything. Except, if I may, don't push for decibels. Less is more.

My god: Less Is More? What will I write next?!

Member discussion